Wed, Jul 27, 2016

Brexit: Minor Disruption or Major Disaster?

The so-called “remain” campaign, which favored continuing EU membership, claimed that such an outcome would have a large and lasting negative effect on the country’s economy. The so-called “leave” campaign, which argued in favor of rescinding the EU link, accepted that there could be some short-run economic turbulence, but held that, in the longer-run, Britain, freed from the shackles of Brussels, might actually be better off in economic terms. Truth lies almost certainly in between.

The immediate market reactions were close to panic, not only in Britain, but also on the European Continent and even further afield (Tokyo’s Nikkei 225 index, for instance, fell by some 8 percent on Friday, June 24, once the referendum’s result was known). Stock markets crashed, exchange rates gyrated, and bond spreads widened. Gradually, however, the panic subsided. In many ways, what happened in late June-early July, was not that different from what had happened in January of this year when some worrying snippets of news from China generated a sharp sell-off of shares in the U.S., Europe and Japan. Yet at the time, after the initial shock, calm soon returned to the markets. The same seems to be happening at present.

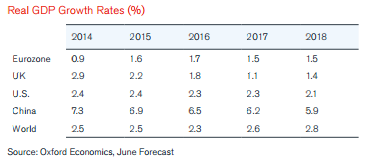

More important than these market tremors are the macroeconomic consequences of the British decision. Over the short- to medium-term these are bound to be negative, particularly for the UK. The future status of Britain’s trade and financial relations with the EU will not be known for several years at best. This is bound to create a great deal of uncertainty and this uncertainty, in turn, will have an unfavorable impact on domestic investment in the UK, on foreign direct investment flows into the country and on the location of many financial activities (presently carried out in the City of London), which could shift to, say, Dublin, Frankfurt or Paris. It is true, however, that a lesser emphasis on fiscal austerity, a possible monetary easing and the Pound’s lower exchange rate should provide some offsets to these negative effects. All in all, Britain is unlikely to experience a full-blown recession, but GDP growth over the years 2016-18 could be some 1 percent below the 21/4 percent average annual growth rate that had been expected in a non-exit scenario. As a result, the Eurozone would also experience a negative effect, if only because of the importance of the British market (some 10 to 15 percent of Eurozone exports go to the UK). This, however, is likely to be quite small. Present forecasts suggest that the Euro area, rather than growing at some 13/4 percent on average between this year and 2018, might grow at only 11/2 percent.

With the passing of time, however, uncertainty will diminish and some of these shortfalls are likely to be made up as investment picks up again. Some permanent losses seem, however, inevitable. Much will depend on the final arrangements that will be reached, but, in all probability, Britain will lose access to the EU’s Single Market (since participation in it requires also the free movement of people, something which British public opinion clearly does not want). This in turn will reduce the level of UK trade below what it would otherwise have been and it is unlikely that the shortfall can be made good by stepping up exports to other countries with which Britain would have to strike time-consuming trade agreements and treaties. A study conducted by the consulting firm Oxford Economics in June 2016, looked at nine possible different scenarios for a post-exit Britain and concluded that all would translate into a lower level of UK GDP by 2030, relative to a no-exit scenario. The orders of magnitude, however, were never huge. Even under the most pessimistic assumptions, output in 2030 would be only some 4 percent lower than it otherwise would have been (it is true that the UK Treasury has come up with a much larger figure, -91/2 percent, but some observers think that there may have been an element of scare mongering behind that estimate, designed to influence voters). In the Eurozone, any permanent negative effect would be negligible (with the exception of Ireland where, in the most pessimistic scenario, the impact could amount to 11/2 percent of GDP).

There are, however, two further consequences from the Brexit vote that need to be born in mind. The first is political. Brexit is clearly strengthening populist parties on the European Continent, particularly in two countries that will soon have elections (France and the Netherlands). Though it is unlikely that other EU members will opt for secession, uncertainty about the future might increase and economic policies, under the pressure of populism, could become more inward looking across Europe, thereby worsening economic performance.

The second consequence relates to the knee-jerk reactions of stock markets which followed the referendum’s result. These were often larger in some European countries than they were in the UK. Italy and Spain’s share prices fell a lot more initially than share prices did in London and subsequently recovered much more modestly, even though the direct negative impact of any UK growth slowdown on these countries can only be minor. This suggests that there is a good deal of nervousness among market operators, nervousness unrelated to Brexit, but arising from the fragility of the European economy and, especially, from the problems of the banking sector in several countries (most noticeably Italy). Any shock, whether it comes from China or from the UK, seems clearly to add to market uncertainty and volatility.

This nervousness is understandable: unemployment remains high, the recovery in output is still very modest and, most importantly, economic policies have exhausted much of their firing power. Should a renewed and significant shock hit Europe, it will be difficult for fiscal policy to counteract it given large budget deficits and high public debt levels almost everywhere (the major exception is, of course, Germany). Nor could much be expected from a monetary policy which is already implementing a sizeable quantitative easing program and has reduced short-term interest rates to negative levels. Under the circumstances, the forecasts shown below are surrounded by significant downside risks, particularly for Europe.

This article was contributed by Andrea Boltho, Duff & Phelps Real Estate Advisory Group Advisory Board Member and Emeritus Fellow of Magdalen College, University of Oxford where he was Fellow and Tutor in Economics from 1977. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of Duff & Phelps.

Valuation Advisory Services

Our valuation experts provide valuation services for financial reporting, tax, investment and risk management purposes.

Real Estate Advisory Group

Leading provider of real estate valuation and consulting for investments and transactions.