Reproduced with permission from Copyright 2020 The Bureau of National Affairs, Inc. (800-372-1033) www.bna.com.

Ted Keen, of Duff & Phelps, discusses why SMEs–and the tax authorities who audit them–require a pragmatic profit split approach that will not require complex (but no less subjective) analyses that could cost SMEs significant fractions of their annual taxable income.

Although SMEs are largely exempt from transfer pricing legislation in the U.K., no such exemption exists in many of the overseas jurisdictions into which they have expanded. In other words, in many countries, SMEs face the same transfer pricing compliance burden as do much larger multinationals. This burden on SMEs deserves consideration, as SMEs account for more than a third of the value of U.K. exports. What’s more, over 97% of U.K. exporters are SMEs.

I am often asked by directors of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs–according to the EU, businesses with fewer than 250 employees or with annual turnover of less than 50 million euros ($56 million)) how to comply with complex transfer pricing regulations.

Overseas transfer pricing documentation requirements for SMEs are complicated by several factors:

- fledgling overseas subsidiaries rely heavily on access to the headquarters’ experienced staff and intangible assets, especially in their first few years;

- for many SME exporters, profit split is the only applicable method; one-sided transaction net margin-based approaches do not reflect the economic reality of the complex interaction between the head office and the subsidiary;

- a profit split analysis like those applied by large multinationals would typically be prohibitively expensive for most SMEs (from 2014–16 the average profit for U.K. SMEs was roughly 200,000 pounds ($263,000)) to conduct; and yet

- many countries (including the U.S.) have no revenue threshold below which SMEs are exempt from producing transfer pricing documentation.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the UN are aware of the problem. In its own Transfer Pricing Manual (Section C.2.4.4.1, p. 411), the UN noted:

“Comprehensive documentation requirements and subsequent penalties imposed on non-compliant taxpayers in a country may place a significant burden on taxpayers, especially on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) who engage in cross-border transactions with overseas related parties.”

In comments to the OECD on proposed revisions to Chapter VII (intra-group services), published by the OECD on June 28, 2018, the Business and Industry Advisory Committee (BIAC) remarked: “…[O]ptions for simplified approaches should be studied and strongly encouraged … for small and medium enterprises (“SMEs”).”

The International Chamber of Commerce similarly noted that:

“The risk for the increasing number of SME’s growing internationally is linked to the fact that they may be less equipped to deal with complex tax environments and would be particularly penalized in the case of revised guidance that either lacks clarity, or is burdensome and requires additional resources to implement.”

Transfer pricing consultant Alberto Pluviano comments (pp. 193–196) on the disproportionate burden that SMEs face in complying with transfer pricing documentation requirements are particularly relevant here. I will not replicate Mr Pluviano’s insightful comments in this article; I will instead attempt to address the question that he and other business groups have posed: how are SMEs with limited resources supposed to comply with the same onerous transfer pricing documentation requirements that apply to much larger multinational enterprises?

The answer is that they–and the tax authorities who examine them–must find pragmatic, cost-effective alternative approaches to their transfer pricing documentation processes. This article explores one possible approach.

SMEs Expanding Overseas

Let’s first look at what happens when SMEs expand overseas. Presumably, the opportunity to expand arises from domestic success that the owners want to leverage in other markets. That expansion often entails establishing a presence in an overseas jurisdiction; that point of presence (an office, branch or subsidiary–for simplicity here we will discuss subsidiaries) will require access to senior management know how, reputation, experience, contacts, IT and management systems, etc.

The nature of the support will vary by business, but it will be some combination of services and intangible property. The support drawn from the head office will be particularly intense in the early years, ideally tapering off as the new subsidiary becomes more established and more self-sufficient, but not disappearing entirely. Indeed, after a few years, the new subsidiary might contribute to the pool of intangibles in the growing group.

The new subsidiary will record revenue which it could not have obtained without access to head office intangibles and support. Support and advisory services should be charged to the subsidiary as appropriate: administrative costs might simply be allocated with or without a mark-up; time spent by experienced employees might be charged with a mark-up to reflect the opportunity cost of their time for the head office, but this will depend on facts and circumstances.

As for the subsidiary’s access to head office intangibles, the head office must be compensated for its value-creating activities, but not necessarily immediately. The parent company might reasonably defer any charge for access to IP, as it would make little sense to extract cash payments from its fledgling overseas office, which might not achieve positive operating profitability in its early years.

Deferred payments are consistent with what we sometimes observe in franchise arrangements between unrelated parties: franchisers may defer collection of certain fees from a franchisee until the latter achieves certain revenue thresholds.

SMEs could adopt this practice; however, if they do so, they should implement a license agreement with their new subsidiaries that contemplates deferred compensation until a subsidiary achieves certain revenue and profitability thresholds, likely to be achieved after several years of operations. Without such an agreement, the SME might run the risk that license payments by the subsidiary to the head office would be indistinguishable from dividends and treated as a non-deductible “hidden profit distribution” by the subsidiary’s tax authority.

Pursuant to that license agreement, the deferred compensation could be calculated as follows: first, calculate the subsidiary’s profitability over the start-up phase. Next, calculate a level of profitability that might be considered “routine” for the specific industry (an industry average or median operating margin, for example), i.e. a level of profitability that the (mature) subsidiary might expect to achieve without access to head office IP.

Any profit or loss in excess of that routine profit should be split between the subsidiary and the head office to reflect the relative value of each party’s contribution to the generation of that residual profit (consistent with BEPS Actions 8–10). What should that share of residual profit be? It should reflect the relative contribution of the head office and the local office in achieving that residual profit in the early years.

The typically heavy reliance of the local office on the head office in early years suggests that the local offices share will be significantly less than 50/50, but equally it will unlikely be zero. Over time, as the local office reaches maturity and becomes more self-sufficient, a sharing of residual profit closer to 50/50 might be more appropriate, with the actual share depending on circumstances.

Illustration–Share of Residential Profit

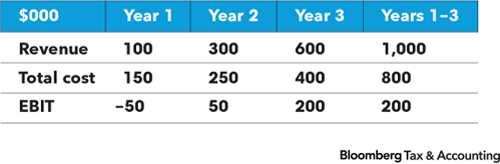

Let’s look at a simplified (ignoring discounting) illustration of this calculation for the first three years of a subsidiary’s operation:

In this example, the subsidiary records a loss in the first year, but over its first three years realizes an operating margin of 20%.

Let’s say in this industry, an operating margin of 10% would be considered normal or “routine.” That implies a residual profit of $100,000 which should be split between the head office and the subsidiary.

Let’s assume further that for the first three years of the subsidiary’s operation, after careful consideration, management concludes that access to the head office’s IP (track record and experience, brand, IT systems, technology, etc.) accounted for 80% of that residual profit, with the remaining 20% attributable to the efforts of the subsidiary in exploiting that IP in its market.

This split of residual profit would likely differ by industry, business model and maturity of the subsidiary, but we will take 80/20 as the appropriate split in this example.

The license fee would then be 80% of that $100,000 residual, or $80,000. Expressed as a percentage of revenue, the license fee would be 8% of revenue over the three-year start-up period, payable at the end of those three years. That would leave the subsidiary with an operating profit of $120,000, a 12% operating margin.

Over the next five years, that license fee might need to be re-calibrated to reflect the greater relative contribution of the subsidiary to its generation of residual profit (we note that this analysis could apply equally to a situation in which the subsidiary reports losses, some of which might be appropriately shared with the head office).

Of course, the subsidiary’s tax authority could challenge this 80/20 residual profit split, which rests heavily on the judgment of the taxpayer’s management team. As a matter of practice, management should document its reasoning behind the 80/20 split as early as possible (management should also document any subsequent movements from 80/20 as the subsidiary matures).

This approach relies heavily on management’s judgment, but is that reliance really any different from relying on more elaborate and expensive “value chain” analyses, complete with responsibility/accountability matrices, to “determine” residual profit allocation?

A debate over the validity of that approach would be the subject of a different article; for purposes of this article, suffice it to say that those analyses rely heavily on management’s prior beliefs of relative value creation within the group, sometimes tending to confirm these prior beliefs rather than challenging them by introducing a completely independent allocation. Perhaps SMEs could bypass this complicated and costly step and rely instead directly on management’s assessment of relative value creation?

Support for management’s subjective judgment over the allocation of residual profit could be derived from the royalty payments as a percentage of the subsidiary’s turnover.

In our simplified example, the 8% royalty rate/license fee might be broadly consistent with observed transactions between unrelated parties in that industry and adjusted appropriately for the subsidiary’s maturity. Royalty rates that appear inconsistent with those observed in transactions between independent parties would suggest a modification to the residual profit split, with due consideration given to whether the subsidiary is in a start-up or more mature phase.

Planning Points

In summary, SMEs–and the tax authorities who audit them–require a pragmatic profit split approach that will not require complex (but no less subjective) analyses that could cost SMEs significant fractions of their annual taxable income.

SMEs need their subsidiaries to accumulate/accrue expenses in the early years for access to head office intangibles and be able to implement an arm’s length charge for those intangibles once the subsidiary has achieved sufficient operating profitability. An arm’s length charge could leave the overseas subsidiary with a routine level of profitability plus a share of any residual profit deemed appropriate.

To implement this strategy, the SME needs to determine:

- the length of the start-up period;

- the appropriate level of routine profitability; and

- the sharing of residual profit over the start-up period and again after the start-up period.

Best practice would be to implement an agreement between the head office and the subsidiary as early as possible that sets out the group’s intention and that allows for a profit split approach that effects a result consistent with the spirit of the OECD Guidelines and the arm’s length principle.

Ted Keen is Managing Director, Duff & Phelps, London.

Valuation Advisory Services

Our valuation experts provide valuation services for financial reporting, tax, investment and risk management purposes.

Transfer Pricing

Kroll's team of internationally recognized transfer pricing advisors provide the technical expertise and industry experience necessary to ensure understandable, implementable and supportable results.

Valuation Services

When companies require an objective and independent assessment of value, they look to Kroll.